The Taproom is a monthly series that explores the rich history of all things beer. It is curated by Pavla Å imková.

By Dotan Halevy

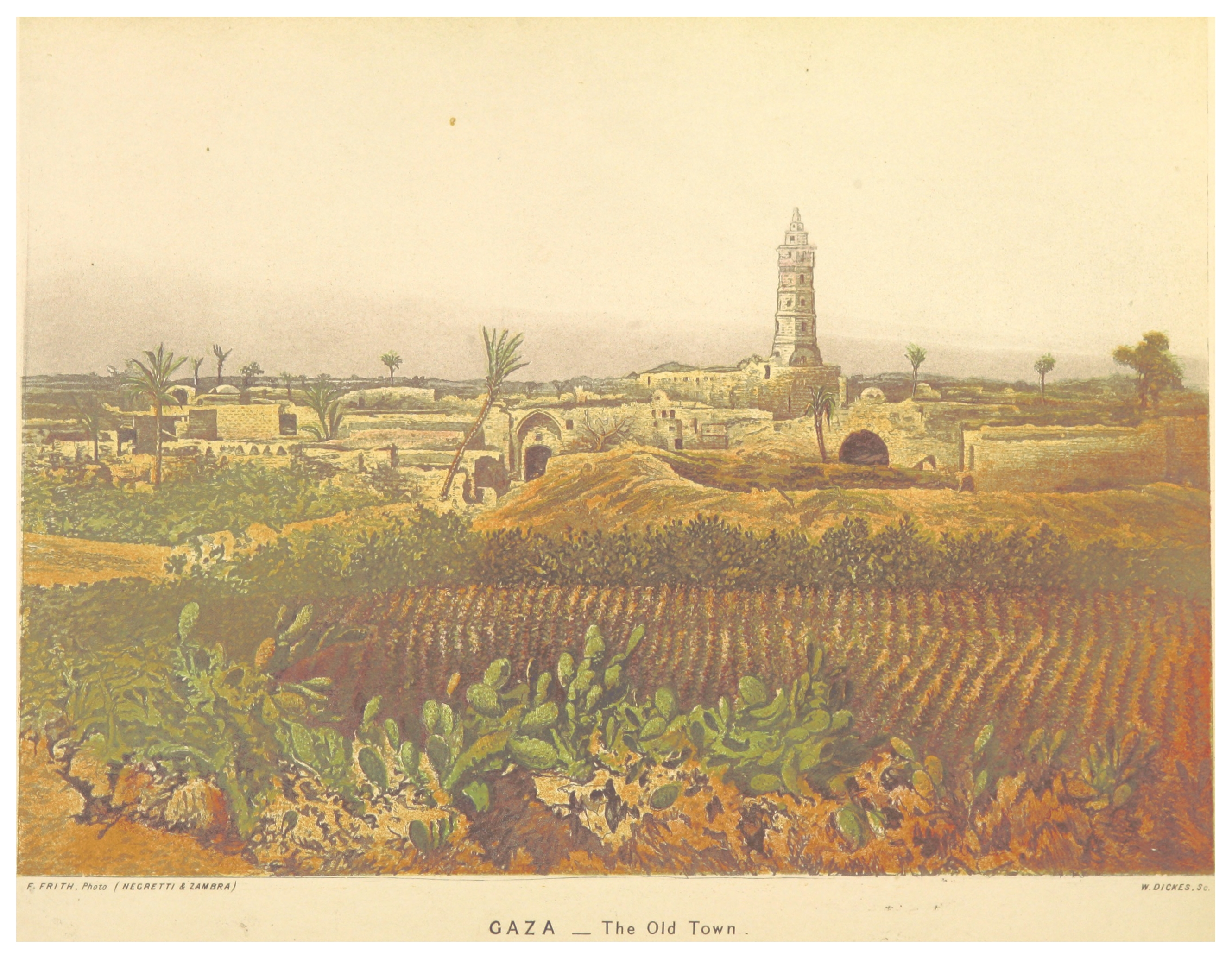

If we could travel back in time to the town of Gaza in March 1886, we would probably be joining a large crowd gathered on the beach to catch a glimpse of the Troqueer, a grain-carrying steamship—a behemoth of thirteen hundred tons—lying on its side about a mile offshore. After the vessel accidentally entered shallow waters and hit the seabed, the gigantic wreck could be seen slowly sinking for several weeks in the open sea facing Gaza’s shore.

This unexpected event drew my attention to an overlooked aspect of Gaza’s history: beer. Nineteenth-century Gaza did not have a real port or even a natural harbor. As the Troqueer and other visiting steamers may have testified, Gaza was indeed a “port-less” port town. Nevertheless, throughout the last quarter of the nineteenth century, this provincial Ottoman town served as one of several suppliers of foreign barley to the beer brewing industry in Britain. The history of the integration of the Middle East into the global economy in the nineteenth century often overlooks such meager towns, where local peasants and merchants grew, produced, and exchanged raw materials. Unlike the cosmopolitan experience of great Mediterranean hubs like Istanbul, Alexandria or Beirut, in small places like Gaza, the outcome of modernity in the age of steam was often economic collapse in the face of the insatiable global demand. Almost overnight, these places were sucked into the global economy and, once they had played their role, were ousted just as quickly. In Gaza’s case, globalization came knocking in the guise of beer and barley.

The Victorian era was a period when the production and consumption of beer in Britain were gradually changing. An approximate starting point was the 1830 Duke of Ellington Beerhouse Act, which facilitated the establishment of retail outlets such as pubs, inns, and victualing houses for selling beer on the British Isles, causing a rapid increase in the production of beer and expanding the demand for its main raw ingredient, barley. The repeal of duties laid on cereals by the Corn Laws in 1846, and the downturn of British agriculture after the great economic depression of 1873, made barley, as well as other grains, mostly an import commodity. As beer became more popular and Britain’s population grew, the demand for foreign barley grew further, pressing British grain merchants to find sources outside the British Isles.

The demand for barley did not only translate into a demand for greater quantities, but also interesting new qualities. During the nineteenth century, the tastes, colors, and textures of beer diversified and transformed as new industrial and scientific methods were introduced in breweries. To mark one such shift, the traditional, dark flat-flavored stout known as Porter was gradually replaced by a new, lighter type of beer. This new “Pale Ale” was faster to brew and easier to preserve than Porter, and the product was therefore sent overseas to the British colonies. With the rapid expansion of the market and a shift in consumers’ preferences, Victorian breweries started competing to manufacture the perfect ale and, consequently, to find the ideal subspecies of barley. In addition, by the 1870s the revolutionary technology of refrigeration had made it possible to move from winter-only to year-round production. This encouraged supplies of barley from areas with an agricultural rhythm that was opposite to that of the British Isles—areas like the Gaza region in southern Palestine, on the southern frontiers of the Ottoman Empire.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the region of southern Palestine saw significant transformations. As part of an empire-wide centralization effort, Ottoman authorities toiled to force sedentarization upon the Bedouin tribes that grazed their flocks between Sinai and Palestine. Partially successful, the Ottomans managed to stabilize the tribal territories, which in turn enabled the Bedouins to cultivate parts of their lands more consistently than before. The main crop sown was barley, which unlike other grains flourishes in semi-arid areas despite the saline soil and scarce rainfall. The Bedouins of southern Palestine proved to be good farmers and within several years turned their surpluses of barley into a cash-crop commodity sold in the markets of nearby Gaza.

By the 1860s, the British press had started to report the arrival of barley-loaded steamships from Gaza to various British ports. As one of the southernmost sources of barley in the northern hemisphere, Gaza could supply the British grain markets with barely as early as May, thus addressing the demands of year-long brewing. Moreover, the arid conditions of southern Palestine meant Gaza’s barley seeds were rich in sugar and low in proteins, a quality well suited to the needs of beer brewing. The barley varieties referred to in the Bedouin vernacular as dhu’l Jammal (the beautiful), al-suhaylawi (from the village of Bani-Suheyle), and abu-safain (the two-rowed barley) were branded by British grain merchants as “Gaza,” “New Gaza,” and the like. Shipping reports tell of an increasing circulation of “Gaza Barley” that, by the 1870s, reached numerous ports all over Britain, and culminated during the 1890s in an annual quantity of around 40,000 tons. That was not much in comparison to other global suppliers of grains, but it was enough to significantly alter the fate of the small town that Gaza then was.

These simple facilities notwithstanding, the expanding barley trade gave rise to a local trading sector in the town and attracted foreign merchants, as well as agents of shipping and insurance companies. In 1905, Britain appointed a consular agent in the town to improve the local treatment of its merchants, and the following years saw several British commercial establishments move into Gaza to benefit from the barley trade. The Ottoman state came to acknowledge the town’s financial potential in the mid-1890s and made plans to build a jetty for more efficient loading and duty collection. The revenues from this duty were earmarked to fund a modern hospital, a sewage system, and roads in Gaza. As a second step, the Ottomans planned to sell plots along the sandy shore for private construction, to enable the rise of a modern seaside neighborhood of Gaza.

In August 1912, the editor of the Jaffa-based Filastin newspaper visited Gaza and later described it as though it was cursed with a biblical spell. “It is neglected by the government, disconnected from the world, abandoned by God,” he wrote. But Gaza was under no spell. In between the barley-sowing Bedouin and the beer-drinking Briton, it was trying to adapt to economic, political, and technological transitions—transitions that, although driven by “modernization” and “progress” in one place, could cause the exact opposite effect in another.

Responses

Would you mind sharing a bibliography or some sources used for this piece? Doing research on a similar topic and would really appreciate it.

Fascinating stuff. Salman abu Sitta’s memoir Mapping My Return contains a description of his father’s large agricultural holdings (pre-Nakba) being used to grow large amounts of barley for export to the British beer industry, and of the British Steele Company trucks coming to collect the sacks of grain.